OPENING: Thursday, November 26 2020, at 20:00 h

DURATION: November 26 – December 4, from 20:00 to 22h

NMG@PRAKTIKA, Klub KOCKA

Dom mladih Split, Ulica slobode 28

Somewhere, at some point, I have already grasped at this analogy before. “Trauma”, a word which in Croatian bears such a disquieting meaning, seems to indicate something else entirely in German: a dream. Whether it be a literal injury or a figurative one, a repressed blight of the soul, the language of this text sees trauma as a malicious occurrence. The German traum can denote a collection of pleasant, carefree images, but it can also stand for a nightmare, or a haunting memory, deeply internalized and encroaching upon one’s dreams. Metaphorically speaking, I would say this is the crucial connection between these two words of similar form and divergent meaning — much like a dream that we can barely recall upon waking, though our day is marked by the mood it leaves behind, whether pleasant or vile, sweet or painful, so does a past traumatic event gradually become distant and shrouded in regard to remembering the facts of it, yet the emotions it stirs up linger like signets. Hard and weighty. In short, the structure of trauma and that of dream, or of “the dream trauma”, are similar — they are fragmentary. I am struck by the permeability of meanings between the two languages here, by the fluidity of words as signifiers of these interwoven states, but even more by the idea that, once the substance of the concepts in question are entirely pared down and viewed purely through the lens of language as the grounds of communication (which entails more than mere speech), the tension and connection between dream and trauma remains subtly intricate, intriguing and disturbing at the same time. The well-known limitations of spoken and written language, with regard to expressing our thoughts and emotions fully, further complicate matters, which makes the process of recalling dreams and traumas all the more challenging, and all the more vital to our common need to face the subconscious. Or rather, the need to embrace it. And just as meanings in language are revealed as both literal and figurative, the realization that speech impairments too share this dual nature represents knowledge which can be employed creatively and channeled according to its spiritual value.

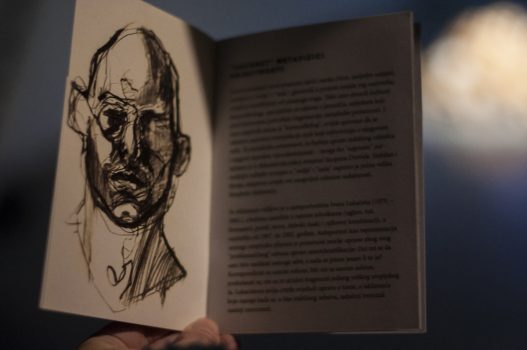

This is precisely what Bojan Koštić, a young artist from Koprivnica, has achieved with his ongoing work titled Das Unbehagen, a concept that originated at the Koprivnica Atelier, before being exhibited at the Scheier building in Čakovec and, prior to its final 2020 installment as part of Mavena’s New Media Gallery, it was shown also at the Praktika gallery in Split’s club Kocka, and at the Prozori gallery in Zagreb (the Silvije Strahimir Kranjčević Library in the Peščenica-Volovčica borough). Some years ago Koštić, a self-taught artist, and Croatian and Latin scholar by profession, had attracted attention (much like his senior Siniša Labrović) at juried group exhibitions such as the Drava Art Biennale, the Istrian Lipa pamti project, and the finalists’ exhibition for the Radoslav Putar Award in 2020 (he had similar success in Split as well, at the Galić salon and the joint exhibition put together by HULU ST and the Zagreb Institute for Contemporary Art). He also stood out with his solo performances, his preferred artform up to now, which he used in order to individualize various social problems and frame them in terms of individual responsibility, but also in order to broaden them and to articulate straightforward, impactful and effective messages for a wide audience. Koštić also works as a freelance video producer and photographer for his own studio, Kontraliht. Additionally, he is office manager for the Koprivnica Atelier, where he has curated exhibitions alongside Tanja Špoljar and Petra Travinić since 2015. He is also co-founder of the Koprivnica Forum for Independent Cultural Organizations, as well as co-founder and program manager for the Koprivnica Performance Art and Theater Festival (2014-2019), and the Pod Galgama organization, as part of which he directed the play Krležin ljubavni kviz, among others.

When compared to all these, one might say, extroverted activities, which also include playing bass guitar for a time in the art-core collective Moskau, and occasional graphic design work, the underlying story of the Das Unbehagen concept is a rather intimate one. On this occasion, Koštić draws inspiration entirely from within, from his own inner world. Namely, from a long-standing struggle with an acquired speech impediment – stuttering, born out of traumatic childhood experiences related to a dysfunctional family environment. In other words, his starting point here is, as it has always been, language as such, which he himself confirmed in an interview for Glas Podravine in November 2018: “[Koštić] emphasizes that his every performance begins with language, with wordplay or an idea embodied by some linguistic phrase. He believes our way of thinking is actually predicated on the language we use.” Koštić’s understanding and use of language in Das Unbehagen is, of course, multifaceted. However, it is laid out through a number of intentionally simple, easily understood and essentially communicative objects, which is evident in the artist’s resistance to any form of mystification when it comes to his well-earned subject matter, in the words of Damir Bartol Indoš. In general, it is worth noting that Koštić’s work, more than that of his contemporaries, relies unambiguously and consciously on the artistic heritage of the neo-avantgarde and of conceptual and post-conceptual art, i.e. on the legacy of the New Art Practice, and the work of the Group of Six Authors – a reliable and direct source of inspiration. In doing so, however, Koštić does not merely refer back to this legacy or imitate it, but rather draws inspiration from the explicitly do-it-yourself spirit of their so-called poor art, hearkening back to the Arte Povera movement of the 60s and 70s, which is in line with his experience growing up in the 2000s, themselves marked by the DIY ethics of post-punk and the independent music scene from which he hails. When considering artists and performers born in the 80s and influenced by their respective regional contexts, these types of ethical and aesthetic choices can be subsumed under a common denominator: a reliance first and foremost on one’s self, one’s immediate local community (at the very least a band), on the resources at one’s disposal, and the idea that one is following one’s desires using only what is readily available, thus transforming limitations into one’s advantages. The emphasis is therefore on the content, which then informs the shape the work will take, and not the other way around. In the prevailing project-based system of cultural politics and production, this kind of outlook all too often fades out of view.

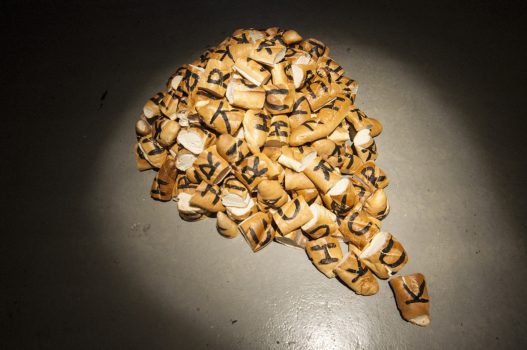

How does Koštić materialize his artistic vision, what procedures does he employ in order to embody his well-earned subject matter, in what way does he transform his individual trauma into a universal and agentive one? Consider first the specific properties of the Praktika gallery, situated underground as part of club Kocka, beneath Split’s Youth Center and Multimedia Cultural Center building. These properties certainly had an effect on the layout of the exhibition, which Koštić in any case varies from place to place, from presentation to presentation. On this particular occasion, the set-up extends beyond the gallery space itself, out onto the steps leading from the ground-floor courtyard outside club Kocka down into the Praktika gallery. It is down these steps that the artist laid out pieces of white bread inscribed with large letters spelling out the word KRUH (Croatian for “bread”), but in random order, so as to convey the limitations, difficulties, and even traps of a sort, that arise in speech and writing, i.e. in language. Just like in children’s tales of old, these “breadcrumbs” lead visitors down underground, into the unknown, symbolizing the subconscious and repressed, only to be coaxed into the Praktika gallery to face the origin of the trauma, or the subject matter of the exhibition, represented by a mound of jumbled up pieces of bread, or letters, or disconnected words, juxtaposed with a video showing the artist’s mouth contorting and seizing as he stutters reading a passage from Sigmund Freud’s Civilization and Its Discontents. The first word in the original German title of this book — Das Unbehagen (“the discontent” in English) — was appropriated as the title for the artist’s work. The incessant stuttering and slow reading pace, the expression of both Freud’s and Koštić’s subject matter through this kind of characteristic, impeded yet recognizable speech pattern, convincingly illustrates the unease which is near immanent to our global postmodern culture, though here we are faced with the biological aspects of this unease, aspects most closely related to culture. The dissonance between everyday experience and the subconscious, which Freud considered the prime determining fact of life, particularly specific to contemporary Western societies, is here epitomized in an uncensored glitch occurring at the intersection of desire and ability, of the striving for clarity of speech and meaning on the one hand, and on the other the limitations brought about by violence, wholly human and distinctly cultural. In place of a live reading performance and an audio-recording reproduced with a ready-made device (a radio typical of the artist’s childhood years, now considered vintage), as was the case with the Prozori gallery exhibition, Koštić now opts for a radio broadcast of his reading, going on air with the local community radio KLFM — Kunst und Liebe Frequency Machine, who also have a recording studio in club Kocka. The sound work produced thereby, in the medium of online radio, has a potentially wider reach than the physical set-up of the exhibition (especially in the context of the ongoing Coronavirus pandemic), and so functions as a virtual expansion of the exhibition and an invitation to attend a real, live event. In effect, this bridges the gap and the apparent disparity between the physical and virtual experience of conceptual and visual art. Moreover, the recording of the Freud passage aims to facilitate a collective acceptance of trauma, thereby circumscribing the dialectic of individual versus collective, a dialectic paramount to the issue of the limits of language and speech addressed by the culturally critical nature of the work.

By creatively using his own language laid bare, his own speech and writing, Koštić manages to articulate the phenomenon of trauma in a very complex manner, while also addressing his own cultural and biological motives and reasons, proclaiming the cathartic experience of facing one’s trauma as an aim not just of his own work, but of art in general, for the individual as well as the community. Seeing as we have entered an age which will, beyond doubt, leave behind substantial planet-wide trauma, any guideposts leading the way to overcoming said trauma, instead of suppressing it, are more than welcome. And if these guideposts are produced by means available to all, they are more than just welcome — they are invaluable.

CURATOR: Bojan Krištofić

NMG PROGRAMME CURATORS: Natasha Kadin, Tina Vukasović Đaković

TRANSLATION: Ivan Berecka

DESIGN: Nikola Križanac

EXHIBITION LAYOUT AND DOCUMENTATION: Tihana Mandušić

DONORS: Ministarstvo kulture RH, Grad Split, Splitsko-dalmatinska županija

MAVENA SUPPORTED BY: Nacionalna zaklada za razvoj civilnog društva, Zaklada Kultura nova

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: KUM, PDM, MKC

http://klfm.org/bojan-kostic-das-unbehagen/